Featured Reports

Tuesday September 19th 2017

Patients, professionals, power and culture

Last week, we looked at "hostage bargaining syndrome" - the propensity of vulnerable patients to deal with powerful and expert clinicians as if negotiating for their health from a position of fear and confusion.

This week's featured report looks at the position of health professionals, and considers how they react to more assertive patients - the ones who are (or are perceived to be) complaining.

Interviews with 41 staff in eight different NHS settings explored how they made sense of complaints and of patients' (including families') motives for complaining.

The authors found that complaints were seen as a breach in fundamental relationships involving patients' trust or recognition of professionals' work efforts. Complaints were most often regarded as coming from patients who were inexpert, distressed or advantage-seeking. Accordingly, care professionals positioned themselves as informed decision-makers, empathic listeners or service gate-keepers.

Troublingly, the authors note that it was rare for interviewees to describe complaints raised by patients as grounds for improving the quality of care.

Taken together, both last week's and this week's featured reports indicate that there is much more to "patient voice" than surveys and "engagement activities". Patients feeling vulnerable and powerless may be too frightened to say anything much. Those who do speak up may be seen by health professionals as troublesome.

Understanding patient experience is not just about feedback systems and action plans. It is also about power relationships and organisational culture.

Tuesday July 23rd 2024

Mesh conflicts of interest

"When medical research and vested interest collide, objectivity, research integrity, and best clinical practices are sometimes the victims."

This opening sentence sets the scene for a paper on industry funding for pelvic mesh research. Specifically, it examines conflict of interest (COI) reporting by US physicians studying mesh safety and effectiveness.

The researchers retrieved 56 papers on mesh from the PubMed database and cross checked the authors with the United States Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments database. They found that 53 out of the 56 papers (95%) had at least one American physician author in receipt of industry funding. The majority of this funding (47 out of 53 articles) was undeclared.

Reviewing the amounts of funding received, the researchers found that "Of 247 physician authors, 60% received > $100 while 13% received $100,000 $1,000,000 of which approximately 60% was undeclared".

They also found that "The majority of publications explicitly stated that mesh was safe and beneficial (57%, n = 32) although only 10 of those 32 substantiated this with evidence".

The paper considers possible reasons for non-disclosure. These, it speculates, could include "journal laxity, researchers’ sense of impunity, conviction that they are not swayed by industry largess, or convincing themselves that funding received was not related to the reported research".

Whatever the reasons, the researchers conclude that "Self-reporting of financial COI by researchers appears to be unreliable and often contravenes requirements agreed upon by international medical journal editors".

They go on to state that "Industry funding both declared and, to a greater extent, undeclared, permeates almost all research on pelvic mesh and almost certainly shapes the quality of and conclusions drawn from those studies. This biased evidence in turn skews the risk benefit picture and potentially drives overuse of pelvic mesh in clinical practice".

Tuesday July 16th 2024

How experience shapes experience

Patient experience is not a "one size fits all". People's expectations for their health, and for the health services they use, are shaped as much by social and cultural factors as by their medical histories and conditions.

This study looks at adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and asks how those might affect health, wellbeing and behaviour in later life.

The report gives examples of ACEs such as child maltreatment or growing up in a household with substance misuse. These are associated with increased risks for health-harming behaviours (eg smoking) and negative physical and mental health outcomes. They also correlate with increased use of health services.

A questionnaire survey of over 1,600 people confirmed previous research findings - for example linking high ACE exposure with greater medication use. Alongside this, the study team found a relationship between ACEs and medication adherence, with individuals with two or more ACEs being more likely to report poor medication adherence.

Another relationship was between ACEs and vaccinations. ACE exposure was linked to having not received all routine childhood vaccinations. This could have implications for vaccine uptake or hesitancy in adulthood.

A further consideration was how comfortable people with adverse childhood experiences feel in medical and healthcare settings. The study found that individuals with multiple ACEs were substantially more likely to perceive that professionals do not care about their health or understand their problems.

Additionally, individuals with four or more ACEs were more than twice as likely to report low comfort in using hospitals, GP and dental surgeries and almost three times more likely to have low comfort in using A&Es compared to individuals with no ACEs.

The report concludes that early life experiences influence individuals’ relationships with health services as adults. Despite increased use of medication, individuals with multiple ACEs may be less likely to take medication as directed, or to use preventative healthcare. They may also experience greater discomfort in using healthcare environments compared to those with no ACEs. These findings, say the authors, are of use in the development of trauma-informed responses to ensure individuals who have experienced childhood adversity are effectively supported to live healthy lives.

Tuesday July 9th 2024

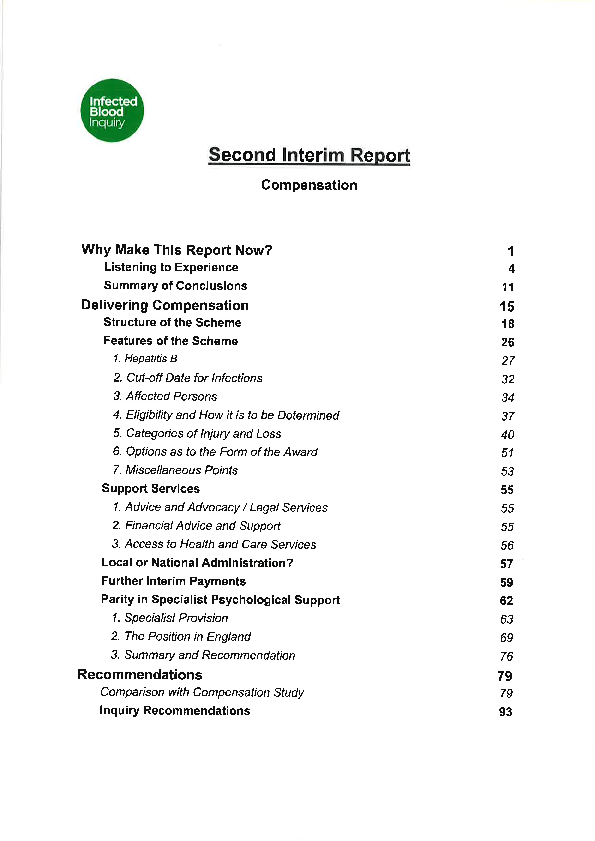

Culture at the heart of harm

This report was published on the 20th May 2024. For a day and a half, it made the news headlines. And then the Prime Minister called the general election, and the news cycle moved on.

The findings of the Infected Blood Inquiry run to seven volumes. There is a huge amount of detail. But anyone interested in patient experience need only glance at the first few pages of this volume to see a recognisable pattern. The report refers to:

- Repeated and ongoing failures to acknowledge that people should not have been infected.

- The absence of any meaningful apology and redress.

- Repeated use of inaccurate, misleading and defensive lines to take which cruelly told people that they had received the best treatment available.

- A lack of openness, transparency and candour, shown by the NHS and government, such that the truth has been hidden for decades.

- Deliberate destruction of some documents and the loss of others.

- Refusal to provide compensation (on the ground there had been no fault).

These are direct quotes from the report.

In an otherwise excellent account, there is one mis-step, where the commentary states that "It will be astonishing to anyone who reads this Report that these events could have happened in the UK". On this point, the authors are wrong - because these events are not astonishing. They are par for the course.

We know this because we have seen it all before - in inquiry reports from Mid Staffordshire, Morecambe Bay, Southern Health, Gosport, Cwm Taf in Wales, the Hyponatraemia deaths in Northern Ireland, Shrewsbury & Telford, East Kent. And in the case of injuries from Sodium Valproate, Primodos and pelvic mesh. And in residential care at places like Winterbourne View and Whorlton Hall.

The lesson that we keep failing to learn is that patient safety is not simply a matter of better training, better guidelines, and better regulation. At some point, the NHS has to get serious about understanding and tackling harmful cultures in healthcare. Those cultures are at the heart of the kinds of avoidance, denial and cover-up referred to in this latest inquiry report. They are harmful to staff as well as to patients. And they need to end.

Tuesday July 2nd 2024

What health literacy means

Health literacy matters. With an ageing population, we have more and more people living with long-term conditions. The best solution for many - and for the NHS - is if people can be helped to 'self-manage' their conditions in their own homes and communities. For that, they need to understand their illnesses, their medications and other matters such as dietary regimes.

But clinicians too have to be helped with their health literacy. Patients who have been living with a health condition for years can often be as knowledgeable, if not more so, than practitioners. And sometimes carers and family members can also have valuable lessons to share with health professionals.

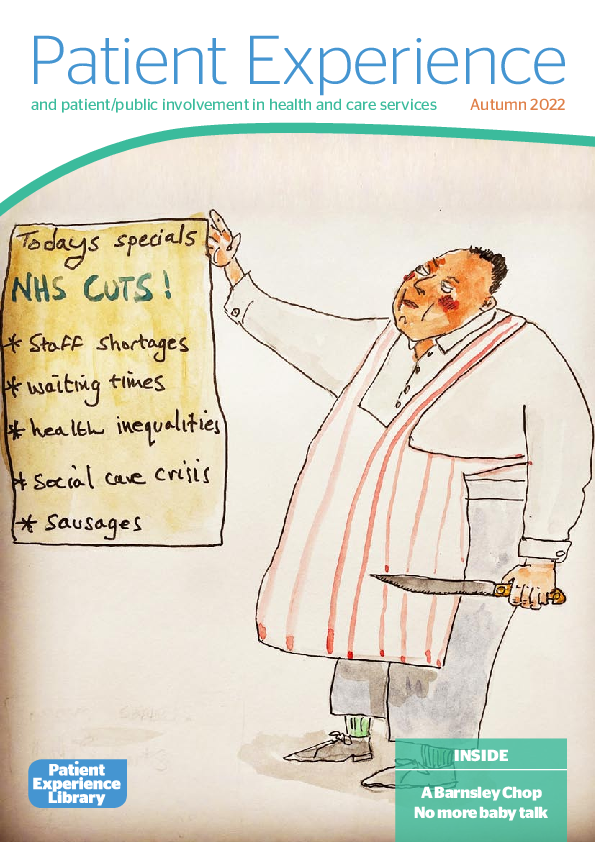

In the latest edition of our quarterly magazine, we hear from Tessa Richards who challenges the notion of a 'one size fits all' approach to health literacy. As a clinician, medical editor, cancer survivor and patient advocate, she has a great deal to offer. But, she says, 'most of the health professionals I interact with assume that I have the literacy of a 9 year old. It’s frustrating and often results in a poor exchange'.

Lesley Goodburn’s husband Seth died suddenly from pancreatic cancer ten years ago. For Lesley, health literacy comes in the form of a series of letters that she wrote to health professionals and organisations. Her aim was to help them understand how it felt to be her or Seth on each of the 33 days from his diagnosis to his death.

Clinicians have expert understanding of the medical progression of disease. But only patients can understand their unique personal journeys through illness. Both ways of knowing have value and only by putting both together can we have truly person-centred care. Perhaps that is what health literacy really means.

As always, the magazine brings you the latest and best patient experience research, packaged in handy summaries for busy people.

Tuesday June 25th 2024

Choice of place of birth

"Choice has been a key aspect of maternity care policy in England since 1993" says this paper. But, it says, "a gap remains between the birthplaces women want and where they actually give birth".

Choice of place of birth matters, say the authors, because "where a woman gives birth will likely affect how she gives birth" - taking in both personal preferences and medical needs. They also note that "research has shown that unfulfilled birth preferences can lead to lower maternal satisfaction and even trauma".

The choices available to women include the hospital labour ward, alongside maternity unit, freestanding midwifery unit and home birth. These birthplaces "sit along a spectrum of medicalisation with different interventions and options available in each setting. The labour ward sits at the medicalised end and home birth at the demedicalised end".

Preferences for any of these locations can be shaped by "social, cultural, historical and medical discourses which are disseminated through friends, family, antenatal classes and the media".

Healthcare professionals are also influential - and "they themselves may be influenced by different ideologies and knowledges of birth, workplace environments and perceptions of risk".

Last but not least, "Experiential knowledge of birth has also been found to be an important factor since women who have a positive experience in their first birth often wish to repeat the same choice, whilst those who have a negative first experience typically desire something different next time".

The researchers found that the majority of study participants preferred to give birth in an alongside maternity unit (AMU) - a midwife-led unit attached to a hospital. This was because of its ability to offer women a compromise between low-intervention care and close proximity to specialist care if needed.

Preferences ahead of labour and birth are, however, different from actual decisions when the time comes. The paper states that "Despite the growing popularity of the AMU as a birthplace preference, the data showed that the majority of women decided to give birth in the labour ward". This, it says "was in line with a wider pattern of medicalisation in the data as women progressed from birthplace preferences to decisions".

The authors conclude that "This lack of congruence could have implications for women’s childbirth satisfaction and as such it is important that maternity care professionals understand women’s birthplace preferences and the reasons behind them". This, they say, "might include if or how elements of the AMU could be incorporated into women’s labour ward births in order to personalise care and facilitate the kind of birth experience they had hoped for".

Tuesday June 18th 2024

Risks and benefits of AI

"Use of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare is on the rise" says this briefing from the Patient Information Forum. And it says that if used as part of a robust production process, AI can streamline the production of health information.

Benefits can include automatic translation of leaflets and videos to help teams serve seldom-heard communities. Automated chat bots can respond to online information requests, both in and out of office hours. And AI can help with accelerated data analysis.

But the paper warns of risks, which, it says "are of critical importance in the health information space where we strive to produce accurate, unbiased, inclusive materials".

One risk is that AI models learn from the data they are given. If the training data contains bias, this is likely to be reflected or compounded in the AI model’s outputs. If data sources are of poor quality, AI outputs may also be of poor quality. Some AI models are trained on out-of-date information. The paper cites the example of the first free-to-use version of ChatGPT which was trained on data published before 2021. So "searches relating to COVID-19 returned drastically out-of-date results".

A specific problem for health is that AI "tends to over-simplify health topics because it lacks the ability to apply context or nuance to its results, or to understand the meaning behind the data". The "high risk of inaccuracy" is not just about the quality of information. It also raises "complex and unanswered questions" about the liabilities of organisations using AI to produce and distribute information.

In spite of these risks, say the authors, "Taking no action is not an option... We need to manage the risks, not ignore them". Their recommendation is that organisations should develop AI usage policies - and the paper points to the kinds of headings and issues that a policy should cover. In the meantime, they say, AI "is not suitable for the creation of health information and content in isolation".

Tuesday June 11th 2024

Drug company payments

This paper starts with the observation that every year medical device and pharmaceutical companies give billions of euros to healthcare professionals and healthcare organisations.

These payments, it says, can create conflicts of interest: "evidence shows that receipt of payments from the pharmaceutical industry is associated with higher prescribing rates, higher prescribing costs, and lower prescribing quality". It adds that "some medical device industry payments have also been associated with legal breaches".

Some European countries are introducing disclosure requirements - however, "the preferred approach to payment disclosure in Europe is industry self-regulation". This, says the paper, creates "transparency limitations".

The authors looked at the MedTech Europe disclosure database to evaluate disclosure through that route.

Its first finding was that between 2017 and 2019 medical device companies in Europe declared €425 million in educational grants to healthcare organisations. However, this "likely underestimates the true extent of medical device industry payments" not least because "many companies are not members of MedTech Europe or the national associations within MedTech Europe".

Another finding concerned accessibility and quality of the database. Here, there were problems with availability of customisable statistics, time limits (data appears to be removed four years after disclosure), and breadth of payment areas (several areas were not included, including consulting, gifts, and charitable donations).

The authors state that the usefulness of the database "is severely limited". They point to a need for "a publicly mandated payment disclosure database" that "could be EU-wide and cover both the medical device and pharmaceutical industry".

They also suggest that a mandated database should cover payments not just to healthcare professionals and organisations, but to patient organisations as well.

Monday June 3rd 2024

End of life conversations

"Conversations about end-of-life care are sensitive and emotionally challenging" says this report from the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO). It goes on to say that any such conversations need to be conducted by appropriately trained professionals, in partnership with patients and families.

The focus of the report is DNACPR (Do Not Attempt Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation) decisions. During the Covid crisis, the PHSO received a higher than normal level of complaints about DNACPR. These revealed various problems, including the fact that healthcare staff were not always well trained. Consequences included the following:

- Patients and their families and carers were consistently not involved in DNACPR decisions during the pandemic and healthcare professionals failed to communicate with them.

- Records were not checked for existing DNACPR decisions.

- DNACPR records did not follow patients to different health settings.

- Patients were not getting support for a range of communication needs.

Almost all of the DNACPR complaints received by the PHSO were from or on behalf of disabled or older patients - the very people most affected by Covid. In one case, the patient had "learning disability" written as one of the reasons for their DNACPR notice. This, says the report, "raises serious questions about the quality of communication and whether a human rights-led approach is being taken to patients' care".

The report makes a series of recommendations on training, communication, regulation and record-keeping. It makes the point that "Having conversations about DNACPR is a legal requirement. Failing to do so constitutes maladministration and a breach of human rights". And, it says, "A rights-respecting, interactive conversation on how someone wishes to end their life is a basic part of end-of-life care provision".

Tuesday May 28th 2024

Breaking purdah

The announcement of a general election puts all kinds of government and public service activity on hold. One feature of the pre-election period is "purdah" - a requirement that public bodies have to communicate with "heightened sensitivity", being sure not to say things that could be deemed "political".

We, however, are not a public body, so we can say whatever we like.

So here is a quick recap of some of the things that have affected people's experiences of health and care services over the last fourteen years.

- NHS waiting lists were at 2.3 million in 2010. By March 2024, over 7.5 million people were waiting for treatment.

- Large parts of England have been described as "dental deserts", with people unable to find an NHS dentist to register with. People who can afford to are travelling abroad for treatment. Others are going without.

- During the Covid crisis in the UK, £10.5 billion was awarded directly to suppliers without competitive tender. Personal protective equipment (PPE) accounted for 80 per cent of the contracts. One beneficiary, to the tune of £200 million, was PPE MedPro - a company in which Conservative peer Michelle Mone first denied, then admitted, involvement.

- The latest British Social Attitudes Survey shows that that overall satisfaction with the NHS is at the lowest level since the survey began in 1983.

There will be a lot of debate about the NHS between now and July 4th. Our focus will continue to be on the people who matter most: patients, service users, carers, families. We hope that election campaigners on all sides will remember the statement from the Francis Inquiry: "The patient must be first in everything that is done".

Tuesday May 21st 2024

Dying in the margins

Place of death is a government proxy indicator of ‘quality dying’ in most Western countries, including in the UK, according to this paper. It goes on to claim consistent evidence that home is the preferred place of death for most people, regardless of their socio-economic status.

In spite of that, "people living in more socio-economically deprived areas... have been shown to be less likely to die at home and more likely to experience (often unscheduled) hospital admissions and intensive treatment in the last few months of their life".

To find out why, this study examined barriers to, and experiences of, home dying for people experiencing poverty and deprivation in the UK.

Its first finding was that there are considerable costs associated with dying at home. People at end of life need warmth - and heating is expensive. They might need non-invasive ventilation, or a bed hoist. Bedding might need washing more often than usual. All of this adds to electricity bills. On top of this are care costs and for some people, taxis if other means of transport are unavailable.

Low income often means poor housing - and study participants described accommodation that was damp, noisy and cramped. This made for oppressive environments that did not offer comfort or safety to dying people.

In spite of these kinds of difficulty, some people stayed at home because it reinforced their sense of self. People feared not being able to personalise a hospice room with pictures, belongings and, in some cases, pets. Identity and autonomy were, to some extent, traded off against physical care needs.

The authors observe that "up until now, insufficient consideration has been given to the social and, crucially, economic capital required to support home dying".

They identify a need for "a strong commitment from the various sectors involved - health, housing, social care, social security, and the third sector - to take a whole-system approach to delivering equity at the end-of-life". And they say that "the elephant in the room here is the neo-liberal political context and the resource constraints which affect how much, as a society, we are prepared to redistribute to those who are worst off and in greatest need at the end of their lives".

Tuesday May 14th 2024

Experience of the NHS App

This report comes from the Patient Coalition for AI, Data and Digital Tech in Health - a group of organisations aiming to champion the patient perspective in digital health. They surveyed 637 people to ask about awareness and use of the NHS App.

Just over three quarters (78%) of respondents were actually using the App and most of those (81%) found it easy to use. The most common uses were ordering a repeat prescription, reviewing personal health records and checking test results.

The quarter of respondents (23%) who were not using the App cited a number of barriers. 10% did not have a smartphone - others had problems with downloading the App, registering and logging in. Many were not aware that it can be accessed via a tablet or laptop, and some were completely unaware of the App.

The report states that "There is a lot of frustration among people who can’t access the services that are listed on the NHS App". More than a third (39%) of respondents wanted to see their test results but couldn't and 36% wanted access to their personal health records. "These responses", say the authors, "highlight how many people still don’t have access to these services".

They go on to say that "While GPs restricting access to information via the App may call this ‘stewardship’, many people in the survey... perceive this as GPs acting as gatekeepers, disempowering patients". There is a sense that "GPs shouldn’t be able to control the flow of information, as this results in a lack of consistency and leads to disadvantage".

The report covers other issues such as the needs of carers who are helping others to use the App. And it touches on issues of data security, noting that some respondents said their use of the App was limited by their concerns about what will happen to their health data.

A series of recommendations concludes with the statement that "some human issues will never be addressed by improvements to the App, and it is, therefore, always important to retain alternative methods of accessing healthcare". In particular, "Healthcare providers need to ensure healthcare services will still be available for use via traditional face-to-face or telephone appointments and make it clearer to people that using digital services is a choice".

Wednesday May 8th 2024

Women's wider health needs

This opinion piece looks at the Women's Health Strategy for England and starts by listing "important progress" - on matters such as hormone replacement therapy and specialist women's health hubs. 2024 priorities include better care for menstrual and gynaecological conditions; improving support for victims of sexual abuse and violence; and more research to tackle maternity inequalities.

Progress in these areas is welcome, say the authors. However, the 2024 priorities reinforce "a traditional view of women’s health as synonymous with women’s sexual, reproductive, and maternal health". This, they say, is a missed opportunity to take a broader view of women’s health.

They cite differences in women’s and men’s experiences of heart attacks, including symptoms, age at onset, effective treatments, and overall outcomes. In spite of this, "blood tests to diagnose myocardial infarction are often not reported against sex specific thresholds".

Similarly, women are at greater risk of diabetes related mortality than men and have a greater risk of complications. And yet women are less likely than men to receive the care recommended by clinical guidelines, and guidelines are not routinely sex specific.

A further example is that women comprise 52% of the global HIV population but continue to be under-represented in anti-retroviral drug trials.

"For conditions that affect both women and men", say the authors, "investments are needed to break the default of research being conducted primarily on men and generalised to everyone else". They go on to say that equitable healthcare for women "is the right thing to do and is financially intelligent".

The article concludes with a view that the Women’s Health Strategy’s priorities "are critical for achieving positive change". However, "to truly take advantage of this opportunity, 2025’s priorities will need to tackle women’s wider health needs".

Tuesday April 30th 2024

Past and future waiting

Waiting times for treatment have a profound influence on patient experience. Four years ago, National Voices showed how people on NHS waiting lists can feel caught in an information vacuum. Some described "fighting" the system, while others talked of "giving up" and "not thinking about the wait" in order to protect themselves and keep their concerns in check.

This report, from the Institute for Fiscal Studies, offers a pre-election briefing, on the basis that "NHS waiting lists are likely to be a key issue in the forthcoming general election". It looks at waiting list data from the last 17 years and presents new scenarios of what could happen to waiting lists over the years to come.

Some of its findings restate known facts. NHS waiting lists were already growing pre-pandemic, doubling from 2.3 million in 2010 to 4.6 million in 2019. The Covid crisis accelerated the growth, with 7.8 million on waiting lists by 2023.

Equally, it will come as no surprise to read that "The NHS and government have failed to achieve most of their waiting list and waiting time targets in England since 2010".

The report states that "Targets set out in the elective backlog recovery plan... to eliminate waits longer than 65 weeks by March 2024... are almost certainly going to be missed". Furthermore, "The longer-running target that 92% of patients should receive treatment within 18 weeks of referral has not been met since September 2015 and looks unlikely to be met any time soon".

Digging into the detail, the study finds big variances across geography and services. Compared with January 2020, the waiting list in December 2023 was 71% higher in the North East and Yorkshire but 113% higher in the East of England. The waiting list for general internal medicine was 2% below its January 2020 level in December 2023, while the waiting list for gynaecology was 109% above.

The authors make the point that "There is a lot of uncertainty over what could happen to waiting lists in England in the coming years, and so it makes sense to consider a range of scenarios". Their most likely scenario is that waiting lists start to fall from the middle of 2024 - but even by December 2027, would still stand at 6.5 million - "far above pre-pandemic levels".

A more optimistic scenario indicates 5.2 million people on waiting lists by December 2027, and a pessimistic scenario suggests little or no reduction from current levels.

A simple analytic allows users to create their own scenarios, factoring in treatment volumes and new joiners. (This could be useful to analysts but will offer little comfort to anyone currently facing the misery of a life on hold.)

The authors conclude that "NHS waiting lists are, and will continue to be, a major policy issue". Their analysis indicates that the next government could inherit a falling waiting list - but, they say "getting the waiting list back to pre-pandemic levels could require more than one parliament".

Tuesday April 23rd 2024

Ways of knowing

"Permanent medical devices are implanted for a wide range of indications across many medical specialties" says this study. It concentrates on one in particular - the vaginal mesh implant used to treat stress urinary incontinence.

Developed in the 1990's and initially seen as the gold standard, the device was before long subject to "a cascade of governmental reviews and regulatory warnings" arising from reports of pain, haemorrhage, infection and more.

The study aimed to explore and understand women's experience of living with complications attributed to vaginal mesh surgery. It found key themes including:

- Loss of dignity. Participants described the humiliation of urine leakage that was the context for surgery, but which could also become a barrier to discussions about post-surgical complications.

- Loss of self. Pain and exhaustion, along with loss of jobs and social lives led some women to feel robbed of present and future selves.

- Dehumanisation. Participants described the need to be treated as a human being, not as body part. Some described being "butchered" by surgeons.

- Trust. Some women felt 'lied to', 'conned' or 'tricked' into surgery. Some were angry that vaginal mesh had been 'sold to them' as 'gold standard', saying that risks had been underplayed.

- Infallibility. This theme describes encountering an infallible and inflexible medical way of knowing. Participants felt that the medical community 'denied' that symptoms were caused by mesh. Some felt treated as if they were 'neurotic', or 'hysterical'.

The issue of "ways of knowing" is crucial. Women described how they sought their own ways of knowing, as well as a sense of solidarity, in online communities. They were sustained by the collective marginality of those existing together in a 'wilderness'. In community, they found their way out of the wilderness and no longer felt alone or 'mad'.

The authors find that women, overall, are asking to be treated as "an embodied whole". Clinicians need to understand that their scientific knowledge (medicine) and craft knowledge (surgical practice) should be tempered with "wisdom" - knowledge that is forged through experience and relationships, and is concerned with moral life and human dignity.

They state that "epistemic injustice - whereby a person’s contribution to the production of knowledge is unrecognised or unjustly excluded... is an ethical issue for careful consideration in healthcare". And "Differentiating anatomy, or indeed pathology, from the experience of a condition may help us to understand the areas of miscommunication that led to widespread mesh use".

This, they say, "has important implications for clinical education in the future".

Tuesday April 16th 2024

Co-opting feminism

"Increased awareness and advocacy in women’s health are vital to overcome sex inequalities in healthcare" says this paper from Australia. But, it says, "Feminist narratives of increasing women’s autonomy and empowerment regarding their healthcare... are now increasingly adopted by commercial entities to market new interventions (technologies, tests, treatments) that lack robust evidence or ignore the evidence that is available".

One example is the AMH hormone test, used in fertility treatment. Levels of AMH in the blood are associated with the number of eggs in a woman’s ovaries. High levels indicate the presence of more eggs and, in theory, higher fertility potential.

But the authors warn that "the notion that AMH testing can enable women to make informed reproductive decisions rests on the incorrect assumption that the test reliably predicts fertility. The evidence now consistently shows that the AMH test cannot reliably predict likelihood of pregnancy, time to pregnancy, or specific age of menopause for individuals".

In spite of this, "persuasive feminist rhetoric is being used on upmarket websites to conceal or gloss over the test’s limitations, as well as the commercial incentives behind the test’s promotion". One website, for example, tells women "You’re not ovary-acting. Understand your hormones and fertility, be the boss of your symptoms and get the expert care you deserve - every step of the way".

A second example relates to breast density - a risk factor for breast cancer. The paper states that "Consumer advocacy groups, often sponsored by large companies... argue that all women must be informed of their breast density to enhance their knowledge and health".

Concerns about population-wide notification, however, include the relatively non-modifiable nature of breast density and the lack of evidence that clinical pathways for women with dense breasts are beneficial. Breast density notification can "increase women’s anxiety, confusion, and intentions to seek supplemental screening", while supplemental screening itself can "include high rates of false positive results", perhaps because of "The unreliability of breast density measurement, which varies across time and by assessor".

Here, the authors point to messaging "evoking fear, guilt, or placing blame on women (eg, 'If you haven’t had a mammogram, you need more than your breasts examined').

The authors argue that "Women’s health is vital and cannot be allowed to be hijacked by vested interests". On the other hand, "persuasive messaging that uses the guise of feminist health advocacy can be difficult to criticise, as legitimate critique may be misconstrued as misogynistic or paternalistic".

They say that "Health consumers and clinicians need to be wary of the simplistic narratives that any information and knowledge is always power". And, they say, "Communication between women and their clinicians is a key aspect to addressing this".

Tuesday April 9th 2024

The data gold rush

"Direct-to-consumer virtual care" is the focus of this Canadian study. It looks at "patient-initiated virtual care delivered by for-profit companies via proprietary software platforms". These services, it says, "allow patients to obtain rapid and convenient access to virtual care without having a prior relationship with the clinician".

It notes that "Patients appear to value direct-to-consumer virtual care services", although it then warns that "much of the research has been commissioned by companies in the industry". Benefits can include better access, convenience, cost savings and positive health outcomes. But some studies have indicated risks including overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

The key question for this paper, though, is the virtual care industry’s data handling practices. That question was explored through interviews with industry insiders and by examining industry websites.

A key finding was that "patient data were highly valued by the virtual care industry and used to generate revenues". While this could help companies to improve and expand services, it could also mean adjusting patient care pathways to promote pharmaceutical products. One study participant described a "gold rush" to gain access to data.

These data handling practices were seen as both normal and acceptable. One participant explained that "these companies are doing what every other company that collects personal information does - using the data to make money".

At the same time, study participants were aware of ethical issues.

One example was that "targeted advertising... could interfere in the patient care journey, with implications for patient health". One participant said "I would like my care journey to be governed by what’s the best care for me, not who paid the most amount of money to get in front of me".

Another concern was privacy. There were "confusing and vague privacy policies [and] difficulty opting out of data uses". De-identification was not necessarily a safeguard: the process was described as "subjective" and some providers were said to be "pretty flexible with it". Furthermore, "if companies combine and share datasets, the extra information also increases the risk of reidentification".

The authors conclude that "Patients, healthcare providers and policy-makers should be aware that the direct-to-consumer virtual care industry appears to view patient data as a revenue stream, which has implications for patient privacy, autonomy and quality of care". And, they say, "Policy-makers should consider how other models of virtual care, as well as enhanced privacy legislation and regulation, can address these concerns".

Wednesday April 3rd 2024

Transparency now

Numerous NHS strategies talk about the importance of being 'patient-centred'. Healthcare staff are often brilliant at this, and platforms such as Care Opinion are full of appreciative feedback from patients who have felt listened to and cared for.

Why, then, do healthcare institutions so often get it wrong? What causes the shift from careful and attentive listening by individual staff to careless and dismissive responses at the organisational level?

Our contributors to the spring edition of our quarterly magazine have both tried to raise serious concerns with NHS bodies and have both run into organisational brick walls.

In 1978, Liza Morton was the youngest baby in the world to be fitted with a cardiac pacemaker. She recently asked to see her paediatric medical records - partly to make sense of her childhood experiences, and partly because the records could hold important information for her ongoing cardiac care. But the records have been destroyed. No-one had thought to tell her, and no-one seems to want to take responsibility.

Kath Sansom has spent years campaigning for women harmed by pelvic mesh. She recently replied to a government consultation on industry payments to healthcare providers - an issue on which mesh campaigners have long been calling for greater transparency. The government has taken four months to respond and has failed to answer any of the points she raised.

We stand by Liza and Kath in their fight for information and for justice. And we condemn healthcare bodies whose reluctance to engage with patients is an affront not just to patients but also to the many, many healthcare staff who work day in and day out for a patient-centred NHS.

Tuesday March 26th 2024

Parity a long way off

"The issue of unsafe discharge from hospital is nothing new" says the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman in the opener to this report. In 2016, "my predecessor had seen patients not being assessed or consulted properly before discharge, carers not being informed and people being kept in hospital due to poor coordination across services".

In mental health services, this can present a risk to a great many people. In 2020 to 2021, there were more than 270,000 attendances at A&E departments in England where a person was recorded as having a primary diagnosis of a psychiatric condition.

During 2021 to 2022 more than 50,000 people were detained under the Mental Health Act, and more than 97,000 people in England were admitted into NHS-funded mental health, learning disability or autism inpatient care.

So how much improvement has the ombudsman seen in the years since 2016? According to this report, not enough. Failings in discharge procedures persist, and "The most common failing... is the involvement of patients, their families and carers in decision-making".

The report presents a series of case studies set out under headings that reveal the problems experienced by patients. These include incorrect information on self-help support, families not updated on the day of discharge, poor record-keeping, poor communication, poor joint working between professionals, and failure to carry out a Mental Capacity Act assessment.

The report makes a number of detailed recommendations, but an overarching concern is that "when these mistakes happen, the health service must be open and honest in its response, acknowledge the impact it has had, and commit to learning".

That ought to go without saying, and it is worrying to see the ombudsman feeling that he has to spell it out.

Equally worrying is the fact that we are now seven years on from Prime Minister Theresa May's call for true parity for mental and physical health. And yet the ombudsman's conclusion is that "reaching the point where mental health is given equal priority to physical health in terms of access and outcomes of care still remains a long way off".

Tuesday March 19th 2024

The death of Patient A

In February 2007 a patient (Patient A) died in the operating theatre of the Salford Royal Hospital. This report states its purpose as "to examine what led to the death of Patient A, and what action the Trust took or did not take following their death".

It reveals a litany of poor professional practice, combined with abuse of power, centred on a spinal consultant, Doctor F. Concerns around this doctor's practice included:

- Negligent and fraudulent clinical practice, leading to serious life-threatening harm to patients.

- Poor clinical practice, including not treating patients in a dignified manner during physical examinations.

- Bullying, intimidation and harassment of colleagues, including unsolicited sexual contact with female staff.

- An extramarital affair between Doctor F and a senior divisional managing director of the Trust, which allowed poor clinical practices and behaviours to continue through undue protection of Doctor F.

The report details harms to other patients of Doctor F. These included a paused operation, with failure to proceed with the next phase for 90 minutes, and no communication with senior colleagues. There were poor preoperative documentation and consent processes. One spinal procedure involved multiple misplaced screws and a life-threatening haemorrhage due to direct vessel damage.

The report's author says that the patients and/or their families should receive a full and transparent explanation and an apology for the level of care they received from Doctor F and the Trust. And, he says, "Lessons need to be learnt from these unfortunate events".

These are depressingly weak recommendations. We know what the lessons are because arrogance, dysfunctional cultures and reluctance to concede error have already been detailed in multiple inquiry reports: Mid Staffs, Morecambe Bay, Gosport, Cwm Taf, Shrewsbury & Telford, East Kent and more. The lessons are clear. It is time we started acting on them.

Tuesday March 12th 2024

The elephant in the room

Patient experience during the Covid crisis was bad. Thousands of people died in isolation from family and friends. Lockdown exacerbated loneliness, anxiety and mental ill-health. Even the arrival of vaccines was, for some people, a cause of fear rather than hope.

Patient experience through the climate crisis will be worse. But while the NHS can claim to have been taken by surprise by Covid, it cannot make the same claim for global heating.

This report from the World Economic Forum explains how scientists have spent at least the last twenty years warning of the impacts of climate change - including those on human health.

Some impacts are well-known - floods droughts, wildfires and rising sea levels. Others, such as the probable arrival in Europe of diseases like malaria, dengue and Zika may not yet have permeated the public consciousness.

Equally, the uneven consequences across population groups may be poorly understood. The report makes the point that "climate change will exacerbate global health inequities. The most vulnerable populations, including women, youth, elderly, lower-income groups and hard-to-reach communities, will be the most affected".

We have seen with Covid how a massive disruption to human health also causes huge disruption to healthcare systems. The report says that climate change will likewise create "a significant additional burden on already strained infrastructures".

The report offers both scenarios and solutions, and issues a clear call to action. "Unlike the case with COVID-19, which took governments and the global healthcare industry by surprise, a unique window exists to adapt and prepare healthcare infrastructures, workforces and supply chains for the escalating impact of the climate crisis".

Importantly, the task is not restricted to healthcare professionals and policymakers: "Collaborative efforts involving multiple stakeholders and industries are essential".

In today's NHS the talk is primarily about waiting lists, workforce and increasingly, productivity. Few, if any, are thinking seriously about the far bigger elephant in the room. But both patients and professionals need to ready themselves.

Tuesday March 5th 2024

Online records access here to stay

In 2021, NHS England announced plans that patients aged 16 and over would have prospective access to their primary care records online, by default. By November 2023, one in four general practice surgeries across England still did not offer online record access (ORA).

Why the delay? Part of the answer, according to this paper, is that "Although patients often welcome transparency, studies show many doctors... express scepticism about patient access".

So this study set out to explore the experiences and opinions of English GPs about the potential impact of ORA on both patients and doctors.

There were plenty of negatives. The vast majority (91%) of those surveyed "somewhat agreed" or "agreed" that after obtaining full online access, a majority of patients would "worry more". 85% believed that most patients would "find their GP health records more confusing than helpful". And 95% "somewhat agreed" or "agreed" that after full online access, a majority of patients would "contact me or my practice with questions about their health record".

Against this were some positives. 70% "somewhat agreed" or "agreed" that a majority of patients would "better remember the plan for their care", with 61% believing patients would "feel more in control of their healthcare". Around half (52%) "somewhat agreed" or "agreed" that a majority of patients would "better understand their health and medical conditions" after accessing their online records or "be more likely to take their medications as prescribed" (50%).

Interestingly, 60% "somewhat agreed" or "agreed" that a majority of patients would "find significant errors in their GP record".

For themselves, GPs concerns included that "I will be/already am less candid in my documentation" (72%); that "patients who read their GP record will be/already have been offended" (58%); and that patient online access would "increase my risk of having legal action taken against me" (62%).

The authors state that "we cannot help but observe a trend towards contrastive views between clinicians and patients". And they say that their findings "suggest patients in England may be vulnerable to negative stereotyping with regard to their capacity to understand and emotionally cope with reading their own health information".

A key implication is the importance of supporting GPs and their staff to become better prepared for talking about and writing documentation that patients will now read. The paper concludes that "in England, patients’ online access to their GPs’ records is here to stay. In the coming months, it will be crucial for GPs, primary care staff and patients to adapt to this radical change in practice".

Tuesday February 27th 2024

Constraining co-creation?

"The last decade has seen an explosion of interest in co-production and co-creation" says this paper. But, it says, "the extent to which these new forms have resulted in meaningful change...is not fully clear".

To explore the issue further, the researchers looked at five local Healthwatch organisations in different parts of England. Local Healthwatch was established to "strengthen the collective voice of local people" and has been described as "a source of genuine co-production".

"The institutional context for co-creation", according to the authors, was "promising". Healthwatch had support at the policy level, and from state agencies, and it drew legitimacy from its status as the "official" conduit for public voice. Additionally, "The ability of Healthwatch to bring the views of marginalized and ‘seldom-heard’ groups to the table formed an important part of their appeal".

The result was that "stakeholders across the whole system had a shared interest in demonstrating that co-creation was happening in a visible, tangible way". So far so good. But here the research team sounds a warming: "this performative need had a strong influence on the activities pursued by the five Healthwatch".

The study found that Healthwatch "took care in how they positioned their organizations... conscious of the need to demonstrate activity and impact". Crucially, "co-creation depended on trusting relationships... which in turn required that they be taken seriously as part of the system rather than be seen as outsiders". From this, they took a view on "which issues were worth pursuing and which were out of bounds".

The approach "seemed to pave the way for constructive dialogue between Healthwatch and others, and secure influence on at least some decisions". "However", say the authors, "this disposition also meant that some activities were shunned". And "Healthwatch maintained a cautious distance from other voices of the public that challenged system organization in a more fundamental way".

Ultimately, "Healthwatch deliberately constrained the scope of their contributions according to their perceptions of acceptability. The full richness of insights, ideas and critique from the breadth of the public that co-creation may offer was carefully filtered before it even reached discussion and decision-making forums: ‘feasible’ solutions took precedence over ‘innovative’ ones".

The paper concludes that "Even though they were not explicitly ruled out-of-bounds, Healthwatch officers knew that to be considered legitimate and serious players in the governance of health and social care, they needed to be selective about which issues they brought to the table". Consequently, "the forms taken by co-creation in practice were largely conservative and constrained".

Tuesday February 20th 2024

A turning point for transparency?

This report is marked "Private and Confidential". It is not hard to see why.

It sets out the findings of an independent review of services at the University Hospitals Sussex Trust, and includes patient safety issues as well as concerns about culture and behaviour.

In spite of that, the report has been posted on the Trust's website, as one of the papers to be discussed at a recent (8th February) Board meeting in public.

That seems like a bold move. The report contains some very worrying findings, including the following:

- A high volume of complaints from patients, and delays in responding.

- Consultant surgeons being dismissive and disrespectful towards other members of staff and displaying hierarchical behaviours towards allied healthcare professionals, particularly junior members of staff.

- Reports of two trainees being physically assaulted by a consultant surgeon in theatre during surgery.

- A culture of fear amongst staff when it came to the executive leadership team, with instances of confrontational meetings where consultant surgeons were told to 'sit down, shut up and listen'.

In the past, and in other Trusts, reviews of this kind have tended to be suppressed. For example, the 2015 Morecambe Bay investigation revealed "the reluctance of the Trust to share the report [of the 2009 Fielding review into the Trust’s maternity services] even when being pressed for it".

It is all the more surprising, therefore, to see the UH Sussex Trust receiving the review team's report in January 2024, then immediately putting it into public Board papers in the first week in February.

In a preamble to the report, the Trust's Chief Executive says "There are some tough messages for staff and us as Trust leaders [but] Problems can’t be solved without first being openly acknowledged".

Everybody knows that things go wrong in healthcare. Far too often, the response is avoidance and denial. This response seems different. Might it be a turning point for transparency? We must, surely, hope so.

Monday February 12th 2024

Groundhog Day strikes again

This review was commissioned in response to a BBC Panorama programme that showed "appalling levels of abuse, humiliation and bullying of patients at the Edenfield Centre in Prestwich". The report says that "The horror of what was shown could not fail to touch anyone who watched the programme".

By the same token, anyone who has read other reports of abusive cultures (Winterbourne View, Whorlton Hall, Muckamore Abbey) cannot fail to get a sense of history repeating itself. All the familiar patterns are there.

We hear that "Some patients and families described not being believed when they raised concerns or complained about the care received... Others shared how they did not always feel safe to disclose concerns, with many accounts of feeling intimidated, undermined, ignored, or fearful that ‘bad news’ was not welcomed".

Another Groundhog Day moment describes "a Trust that was not sufficiently focused on understanding the experience of patients, families and carers... The lack of both curiosity and focus on improvement led to missed opportunities for organisational learning".

In common with health professionals elsewhere, staff at Edenfield talked of "feeling exasperated, tired of not being listened to and disconnected from the Trust leadership... staff have felt fearful to speak up for many years".

Of course some patients and families tried to raise concerns. But "there was a lack of clarity and accountability throughout all the complaints process... making a complaint was discouraged".

The new Chief Executive at the Trust has said 'We cannot change the past, but we are committed to a much-improved future".

It is true that we cannot change the past. But we can learn from the past. From Mid Staffordshire, Morecambe Bay, Gosport, Shrewsbury & Telford, and East Kent. From Cwm Taf in Wales and the hyponatraemia deaths in Northern Ireland. From the widespread harms caused by Primodos, Sodium Valproate and pelvic mesh. From Letby, Paterson and Fuller.

The literature on harm - and harmful cultures - is extensive. It contains all the lessons we need. Healthcare providers need to stop trotting out wearyingly familiar apologies, and start taking seriously the job of learning from patient experience.

Monday February 5th 2024

Misinformed choice

"Informed choice" is a principle enshrined in the NHS Constitution - a document based on medical ethics and law. Informed choice means that patients should have sufficient information and understanding before making decisions about their medical care.

It is surprising, then, to see NHS England announcing a potentially misleading addition to the NHS App. Heralded as a "new feature to improve patient experience", the app will now show mean (average) waiting times for treatments at English acute Trusts.

Official figures published via the NHS England website, however, do not use averages. They use a "92nd percentile" figure. Why? Because under the NHS Constitution, 92% of people waiting are meant to be treated within 18 weeks. And the 92 percentile figure is always higher - much higher - than the average.

NHS England says that the average waiting times information will help "by better informing patients about their care". But unsurprisingly, some disagree.

Patient Safety Learning cites "senior figures close to the project" as saying that "the NHS App will give patients 'disingenuous' and 'misleading' information about how long they can expect to wait for care".

The President of the British Orthopaedic Association agrees. He has said that "as an example, the mean average waiting times for patients could be around 22 weeks whereas the 92nd percentile figure is 63 weeks, showing just how far apart these two metrics are". He goes on to say that "It is unacceptable that patients may be given such false hope".

So there seems to be a double standard at work. Official statistics - aimed at policymakers and practitioners, use the helpful and reliable 92nd percentile figure. But the NHS App, aimed at patients, offers averages that could be misleading.

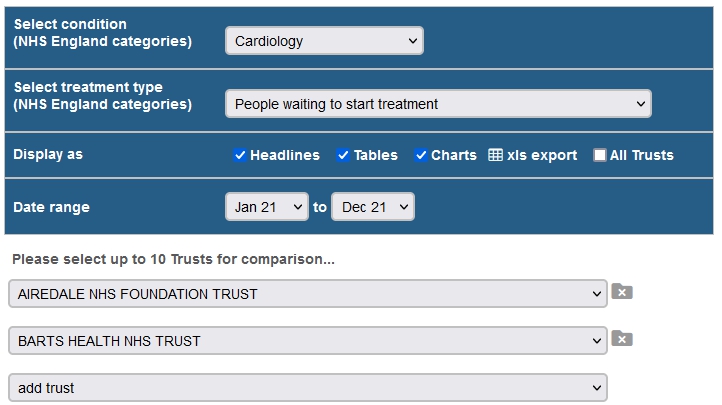

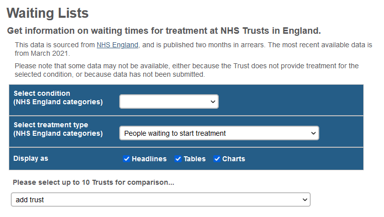

We think that informed choice is important. So we have taken the more meaningful official figures and made them available via our open access waiting list tracker.

The tracker gives instant access to waiting times for all treatment types at all acute Trusts across England. It enables side-by-side comparisons of waiting times at different Trusts. And it includes a headlines summary that can be printed off as a handy aide-memoire. We think all of that might be more useful to patients than a simple figure on average waits.

By putting averages into the NHS App, NHS England risks undermining the NHS Constitution's promise of informed choice. It also risks undermining public confidence and trust. And that is not something that a struggling NHS can afford to do.

You can use our waiting list tracker here.

Tuesday January 30th 2024

Pharma's levers of power

"The pharmaceutical industry is one of the most powerful industries in the nation" says this US study. The industry has various levers of power, but this report looks at one in particular: "the billions in grants the industry has given out to the most powerful advocacy organizations in the country".

The study was conducted by Public Citizen, which describes itself as "a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization". Its aim is "to ensure that government works for the people - not big corporations".

The authors analysed hundreds of publicly available documents and built a dataset including corporate and foundation grants given out by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) and its member companies.

They discovered $6 billion in total grants dispersed by the PhRMA Network to more than 20,000 different recipients from 2010 through 2022. 13 of the nation’s largest and most powerful patient advocacy organisations received $266 million between them.

The view of the authors is that "when a patient advocacy organization stays silent on a debate on drug prices, publishes an op-ed supportive of a PhRMA Network position, or endorses a questionable drug, it is reasonable to wonder if the money they received... played any role in their decision making".

This spirit of curiosity led to findings including the following:

- The American Cancer Society received $6 million from AstraZeneca, $4.7 million from Merck, and $3.4 million from Pfizer, all manufacturers of expensive cancer drugs.

- The American Diabetes Association received more than $11 million in grants from Sanofi and more than $7 million from Eli Lilly. Along with Novo Nordisk, the companies control 90% of the insulin market globally.

- One of the nation’s most prominent spinal muscular atrophy organisations, Cure SMA, received more than $5.8 million from Novartis, the manufacturer of the SMA gene therapy that costs $2.25 million per dose.

Additionally, Public Citizen found many op-eds that were published by PhRMA Network grant recipients criticising US government efforts to rein in drug prices. In some cases, the author and grant recipient received a grant around the time of the op-ed’s publication for 'advocacy".

Furthermore, 740 lobbyists were hired by both grant recipients and members of the PhRMA Network. These grant recipients received $577 million from the PhRMA Network.

In conclusion, the authors state that "The PhRMA Network companies are not mission-driven charities. They are some of the largest and most profitable companies in the world, hyper-focused on returning value to shareholders. It’s impossible to know how much the money affects the decision-making process of the grant recipients. But it is hard to believe $6 billion had no effect".

Tuesday January 23rd 2024

Building trust

"The NHS is looking to advances in digital health technologies and data to help tackle current pressures and meet rising demand" says this report from the Health Foundation. "But", it says, "ensuring new uses of technology and data have the backing of the public is critical if they are to become business as usual".

The authors surveyed 7,000 members of the public to test their views.

The good news is that people are generally supportive of technology in healthcare. Over half of those surveyed (51%) said that the NHS should make more use of self-monitoring devices, such as blood pressure or heart rate monitors. And nearly half (48%) said the NHS should be making more use of electronic health records.

There was less support, however, for the use of chatbots to check symptoms or get health advice and less support for video conferencing to speak to a health professional. The authors note the difference between technologies aimed at supporting the public, and those that might be perceived to come between the clinician and patient.

As far as healthcare data is concerned, the survey found that nearly two-thirds (61%) knew ‘very little’ or ‘nothing at all’ about how the NHS is using the health care data it collects.

In spite of this, two-thirds said they trust GP practices, local NHS hospitals and clinics and national NHS organisations with their health data ‘a lot’ or ‘moderately’. But national and local government organisations and health technology companies are less trusted. There is, says the report, a need to "grow trust in organisations with currently low trust levels".

The authors conclude that "Over the coming years, policymakers and NHS leaders will need to prioritise meaningful public engagement on the future of technology in health care". And they say that "it is important that this public engagement is inclusive, seeking out the voices of those who can often be excluded in public consultations".

Tuesday January 16th 2024

Detecting patterns of harm

David Fuller worked for the NHS for 31 years. "His employment", says this inquiry report, "started only two years after he committed the brutal murders of two young women in Kent, whose deceased bodies he sexually assaulted". He went on to commit 140 known offences against deceased women and girls in the mortuaries at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust.

How can such appalling crimes have gone undetected for so long? The report offers a series of answers - and as with so many instances of large-scale avoidable harm, they fit a recognisable pattern.

The first is that "This is not solely the story of a rogue electrical maintenance supervisor. David Fuller’s victims and their relatives were repeatedly let down by those at all levels whose job it was to protect and care for them".

That statement has echoes in the Cumberlege review of harms from products including pelvic mesh. It said "The issue here is not one of a single or a few rogue medical practitioners... It is system-wide".

The Fuller report notes that "The culture... at Tunbridge Wells Hospital, as observed by the Inquiry, was not one of questioning and curiosity. There was a lack of curiosity about David Fuller’s work behaviour in relation to the mortuary".

That parallels the inquiry into Ian Paterson, the jailed breast surgeon: "While we heard from nurses that 'everyone knew', some professionals told us that they were unaware that Paterson was performing inappropriate treatment until formal investigations were underway. There is, therefore, a question regarding professional curiosity".

There is evidence of siloed working at Maidstone and Tunbridge: "mortuary staff felt ignored by senior managers and separated from the rest of the Trust... mortuary staff were 'functionally isolated'.

Something similar happened at East Kent, the scene of harms in maternity services, where "Canterbury was full of the great and the good consultant-wise, and they sort of looked down at Margate and Ashford and everybody knew that as well".

At Maidstone and Tunbridge there was "a culture... in the mortuary where Standard Operating Procedures were routinely ignored and security breaches were not thoroughly investigated".

That takes us back to Paterson, where "The appraisal processes for Paterson did not pick up his poor practice...There were policies and guidance in place, but these were not implemented".

The report of the Fuller Inquiry offers other examples of harmful cultures at Maidstone and Tunbridge, and they all fit with patterns that are - or should be - well known by now across the NHS.

We need to learn from these patterns. That means rejecting simplistic notions of "rogue operators" and instead taking on the harder work of tackling system-level weaknesses. It means understanding that lack of professional curiosity creates opportunities for wrongdoing. It means acknowledging that siloed practice is dangerous practice. It means knowing that when policies are ignored, harm ensues.

The patterns are clear, and every single inquiry report - Mid Staffs, Morecambe Bay, Shrewsbury and Telford, East Kent, Paterson, Letby, Fuller - makes them clearer. An NHS that keeps promising to learn the lessons needs to start learning what patterns of harm look like.

Tuesday January 9th 2024

Telling stories

'Storytelling' is often seen as an important way to communicate patient experience, and rightly so. But how can storytelling be done well?

In this edition of our quarterly magazine, Sue Robins makes the case for safe spaces for patient storytellers (page 3). In her own experience as a speaker, she has encountered tokenism, a lack of care and sometimes, a lack of common courtesy.

At other times, she has found practical and emotional support, and a genuine recognition that her 'stories' are something more than mere edutainment.

Lynn Laidlaw on page 4 recounts the experience of being part of a research team seeking the stories of people who are clinically vulnerable to Covid. As a clinically vulnerable person herself, this opened up questions of identity and competence.

Could she objectively analyse stories that reflected - or diverged from - her own experiences? And how could she occupy the role of 'expert by experience' and 'researcher' simultaneously? Questions like these are vital to good quality coproduction in research.

A special feature on our evidence mapping work (pages 5 and 6) reveals the patchy way in which people’s healthcare stories are brought into the patient experience evidence base. While medical research has clear prioritisation processes, evidence-gathering on patient experience is, essentially, a free-for-all. We show how inequalities in health are linked to inequalities in research, and suggest some solutions.

As always, we also bring you the latest and best patient experience research, packaged in handy summaries for busy people.

Tuesday December 19th 2023

An opportunity lost

The NHS has no shortage of strategies. Many of them - Transforming Community Services, the Five-Year Forward View, the Long-Term Plan - have made the point that the UK has an ageing population, and a growth in long-term conditions. The strategic response depends in large part on encouraging people to "self-manage" their conditions in their own homes and communities.

Central to self-management are homecare medicines services. These provide up to half a million people with the medicines they need, along with any necessary help to administer them.

This House of Lords report examined these services and found a great deal of room for improvement.

A key concern was safety. "No one", says the report, "not the Government, not NHS England, not patient groups, not regulators - knows how often, nor how seriously patients suffer harm from service failures in homecare".

Another was financial. "The Government does not know how much money is spent on homecare medicines services. It is therefore impossible to make any assessment on value for money. Given that the figure is most likely several billion pounds per year, this lack of awareness is shocking and entirely unacceptable".

The report points to "serious problems with the way services are provided. Some patients are experiencing delays, receiving the wrong medicine, or not being taught how to administer their medicine".

Homecare medicines services are mainly provided by private companies. So in some cases, the taxpayer is effectively paying for the service twice - once for the private provider to deliver it, and again for the NHS to pick up the pieces where private providers fail.

"Most concerningly", say the peers, "we found a complete lack of ownership of these key services... no one person or organisation was willing to take responsibility for driving improvements or exploiting the full potential of homecare medicines services to bring care closer to home. Simply put, no one has a grip on this".

The report makes recommendations on transparency, procurement, enforcement of standards and digital infrastructure. It concludes, with a masterpiece of understatement, by hoping that the analysis will "be of assistance" to NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care.

Tuesday December 12th 2023

Unequal waiting

After the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, NHS England asked integrated care boards (ICBs) and NHS trusts to address health inequalities as part of tackling growing waiting lists for elective care. This report looks at three Trusts and ICBs to see what progress has been made.

A fundamental first step was for providers to disaggregate their waiting list data, to identify patients by ethnicity and deprivation. Two years on from NHS England's ask, only one of the three Trusts had achieved this. None of the ICBs were reporting disaggregated waiting times data to their board.

There were also barriers to the idea of a new approach. In one Trust, "work to reprioritise waiting lists had stalled because of resistance from clinicians". In the other two, "leaders were concerned about how clinicians would react to the work".

Data issues were another problem. These included poor quality ethnicity coding, and limited analytical capability.

Surprisingly, there appear to be no formal performance management or accountability structures for inclusive recovery within NHS Trusts or at ICB level: "health inequalities were not part of accountability conversations with NHS England". Moreover, "Interviewees were uncertain about what a meaningful measure of success would be, and noted that the policy on taking an inclusive approach to reducing the backlog did not set out a clear vision for this".

In spite of all this, there were some pockets of success. But these were more in terms of simple improvement projects than systemic change. And they were led not so much by executive teams as by individuals with a passion for addressing inequalities. The report makes the point that "the NHS needs to harness that enthusiasm and give these leaders the tools and ideas needed to make change in their clinical areas".

The authors conclude that "Waiting lists are one place where the causes, experiences and consequences of health inequalities coalesce. If the NHS is serious about addressing health inequalities, it needs to address inequalities on waiting lists for elective care as part of that".

Tuesday November 28th 2023

Journaling experience

In patient experience work, it is common to hear talk of people who are "hard to reach".

Sometimes the phrase is seen as a convenient excuse for not trying hard enough. But some people really are hard to reach because of severe illness, or mental incapacity.

In this article, David (an intensive care patient), tells how the practice of diary-keeping enabled family members and staff to understand what he was experiencing as he emerged from six weeks of coma, ventilation and proximity to death.

As he recovered, David found himself disorientated and prone to vivid nightmares and hallucinations. At times he was overwhelmed by anxiety and paranoia. Through all of this, his partner Rose's diary, along with his own scrawled questions and notes, helped them both to make sense of their fear and bewilderment.

Rose also documented clinical updates, making her own record of procedures, treatments and clinical signs, along with notes on David's reactions and progress.

The resulting booklet, says David, "helped me to appreciate the outstanding care both I and my family had received in those weeks". It also enabled him to "create some sort of timeline and extract the true memories from my fragmented and delusional recall".

Since leaving hospital, the diary remains a valuable resource, helping David to live with the continuing consequences of his illness. "The power in these entries lies in their ability to help me understand how dire my prognosis was. When I get frustrated with my life situation and residual health issues, finding myself struggling to move forward, I can look back to these early days and see how far I have travelled in my recovery journey."

David comments that "Reading and reflecting on my diary has often grounded me, helped ease my anxiety and prevented me from slipping further into the grip of depression, proving in my case, the ongoing mental health benefits of the diary".

David finishes with a request for health professionals: "In a world where intensive care is provided at huge expense, an ‘ICU diary’ costs a small amount of time, the price of paper and a pen and a moderate amount of teamwork. I hope I have demonstrated that the cost to benefit ratio for your patient is undoubtedly in its favour".

Tuesday November 21st 2023

A struggle every day

"A struggle every day' is how one respondent to a Healthwatch survey on hygiene poverty described her experience of homelessness.

That short phrase no doubt encompasses a multitude of other experiences. Healthcare policymakers and providers need to hear those experiences if they are to improve services for homeless people, in line with NHS England guidance.

This begs a question: where is the evidence on the healthcare experiences of people who are homeless or insecurely housed?

Is it easily accessible, or scattered across multiple websites and hidden behind journal paywalls? Is it comprehensive, or are there gaps? Is new research being steered towards the accumulation of new knowledge, or is there duplication and waste?

To begin answering these questions, we looked through two and a half years’ worth of studies and reports. We found extensive duplication - particularly on the question of homeless people’s access to health services. And we found areas such as hygiene poverty where the evidence was, to say the least, thin.

This latest report in our evidence mapping series looks at the implications for national NHS bodies and for research funders, and suggests ways to get better value and better learning. And if you want to explore the evidence base for yourself, you can skip straight to our interactive map to see what it looks like.

Tuesday November 14th 2023

Slaying dragons

Patient safety seems to be a permanent feature of news headlines these days.

Large scale harm in maternity services has been revealed at Shrewsbury and Telford, and at East Kent. There is an ongoing investigation at Nottingham. There have been deaths of babies at the hands of Lucy Letby. And then there are individual examples, such as the avoidable death from sepsis of Martha Mills.

So what is going wrong with patient safety? How can there be so many calamitous outcomes across so many services and locations?

This commentary from America offers food for thought.